When it comes to improving poor reading skills, one of the most important things ELA teachers can do is choose texts that match students’ abilities. Finding that balance where a text is challenging but not overwhelming can make all the difference in helping students build reading confidence rather than discouraging them.

But how do you know if a text is appropriate or not? When judging a text’s difficulty, we usually look at three different criteria: quantitative measures, qualitative measures, and reader and task considerations.

Quantitative Measures

The first criteria is all about numbers. Quantitative measures rely on algorithms that analyze specific text elements to determine difficulty levels. There are two main scoring systems: the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Readability formula and Lexile measures. It’s important to note that both of these rate a text’s complexity based only on technical details like word and sentence complexity, not by the literary merit of its content.

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Readability

The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Readability formula is used to estimate the difficulty of a text by calculating two factors: average sentence length (ASL) and average number of syllables per word (ASW). The formula looks like this:

(0.39 x ASL) + (11.8 x ASW) - 15.59 = Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level

The resulting number corresponds with a school grade that shows the education level needed to comprehend the text. For instance, a score of 8.0 means that an eighth-grader should be able to read it easily.

Lexile Measures

A Lexile measure refers to either the difficulty of a text or a reader's ability to understand it. It’s expressed as a number followed by an “L,” like 960L.

Like Flesch-Kincaid, a Lexile measure shows how challenging the material is, but it doesn’t reflect the depth of the ideas in the content. Some low-scoring texts are packed with complex ideas, while some difficult texts are easy to grasp.

When applied to students, a Lexile measure indicates how well they can understand a text. A higher Lexile level means better comprehension skills. The general rule is to assign texts that are close to a reader’s Lexile level, usually no more than 50L above it, for maximum comprehension.

Qualitative Measures

As the name suggests, qualitative measures of text difficulty rate a text’s features that can’t be measured by formulas, like its content, language, and structure. Qualitative measures are usually assessed by educators using scoring rubrics or guidelines based on these four elements:

Levels of Meaning: This looks at whether the text has a single purpose or multiple meanings. For instance, a fictional work that needs deep analysis to grasp its meaning is harder to read than one that tells a simple story.

Structure: Texts written with predictable structures like chronological order or single points-of-view are easier to understand than ones that use nonlinear timelines, multiple perspectives, and other unconventional or complicated forms.

Language Conventionality: Readers are more likely to comprehend texts that have familiar language and clear sentence structures over ones that use archaic terms, domain-specific vocabulary, or figurative or ambiguous language.

Knowledge Demands: Texts that describe everyday experiences are easier to read than ones that require background knowledge of history, culture, or specialized topics.

Reader and Task Considerations

The third criteria, reader and task considerations, relies on your expertise as the teacher to decide whether a text is right for your students. When evaluating a text, you need to look at an individual student’s abilities and the purpose or context in which the text is used. Try answering these questions:

Reader Considerations

- How interested is the student in the text or topic?

- Does the student have prior knowledge or experiences related to the subject?

- What’s the student's current reading proficiency level, including vocabulary knowledge, decoding ability, and comprehension strategies?

Task Considerations

- What’s the goal of the reading assignment? Is it to analyze a theme, retain information, or simply enjoy a story?

- What kind of thinking and understanding does the reading task demand?

- Are there discussion prompts, guided questions, or vocabulary support to help students parse the text?

Using Reading Literature to Choose Appropriate Texts for Your Students

With Reading Literature, it’s easy to pick the right texts for your curriculum without spending hours researching whether students will be able to read them or not. Intended for grades 9-12, this series collects popular short stories and poems into single volumes appropriate for each grade level.

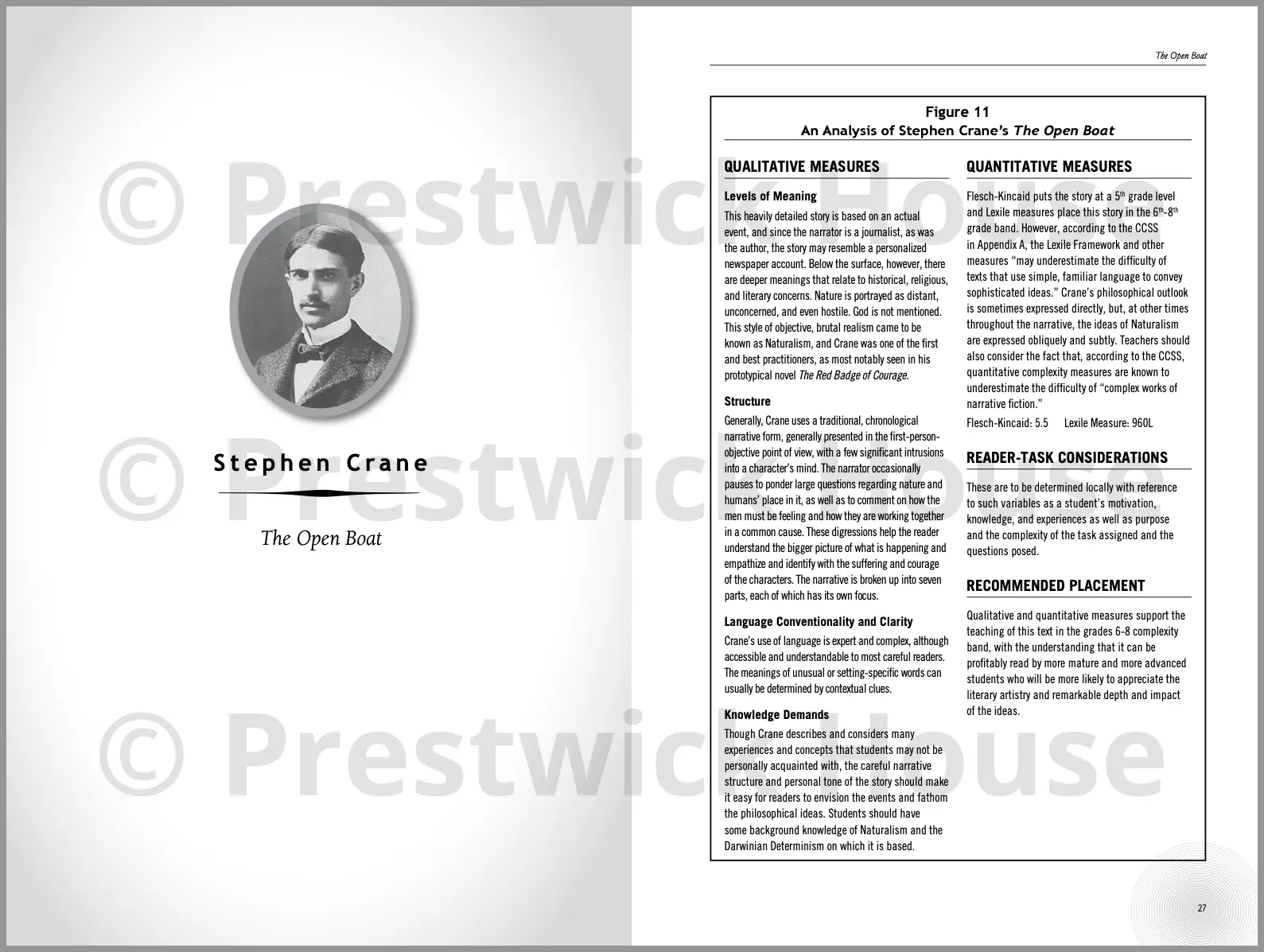

In the Teacher’s Edition, each reading selection begins with a quick analysis of its complexity, making it easy for you to decide if it’s the right difficulty level for your students. An example explanation for Stephen Crane’s “The Open Boat” is below:

Over the course of the series, your students can read exemplary written works such as:

- “Sonnet 73,” by William Shakespeare

- “The Story of an Hour,” by Kate Chopin

- “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” by John Keats

- “Grass,” by Carl Sandburg

- “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” by Ambrose Bierce

- “The Yellow Wallpaper,” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- “Because I could not stop for Death,” by Emily Dickinson

- And more!

Every text is annotated, giving students the support they need to handle challenging language, old vocabulary, obscure allusions, and other elements that could make understanding these important works more difficult.

Accompanying short-answer questions push students to analyze the text deeply, asking them to apply what they’ve read and examine how authors skillfully use literary devices to make compelling stories.

In search of nonfiction reading selections? Check out the corresponding series, Reading Informational Texts.