As ELA educators know, literacy is the foundation for academic success. But over the past few years, there’s been a measurable decline in students' reading abilities across the country. With a growing number of students showing underdeveloped literacy skills, especially at the secondary level, many schools and districts are rethinking the ways to approach reading instruction.

To better understand this issue, we reached out to our ELA teacher subscriber base with a simple survey asking about their experiences teaching reading to modern students. We wanted to learn what they value in a reading curriculum as well as the strategies they personally use to support struggling readers.

Here’s what they shared with us!

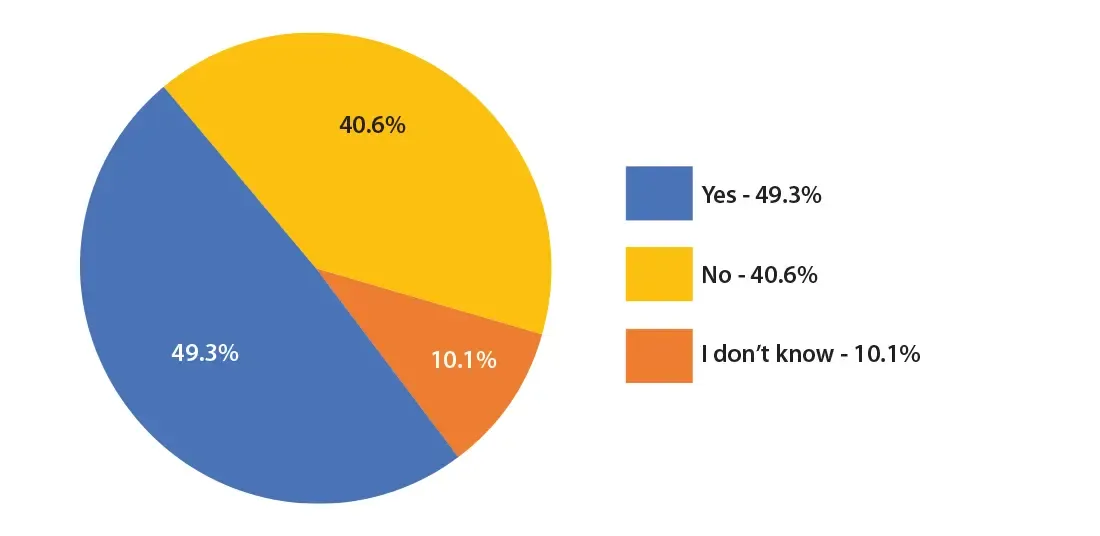

In the past three years, has your school or district revised the reading curriculum?

The conversation on how to fix the reading issue really took off in 2018 when education journalist Emily Hanford published her radio documentary Hard Words: Why Aren’t Kids Being Taught to Read? Her investigation revealed significant flaws in popular teaching methods like whole language and balanced literacy approaches.

Related Post: 3 Important Frameworks Behind the Science of Reading

Since the release of Hanford’s report, many schools have begun shifting away from these methods in favor of phonics-based instruction and other research-backed strategies related to the science of reading.

When asked if their school or district has revised the reading curriculum in the past three years, 49.3% of survey respondents said yes, 40.6% said no, and 10.1% weren’t sure.

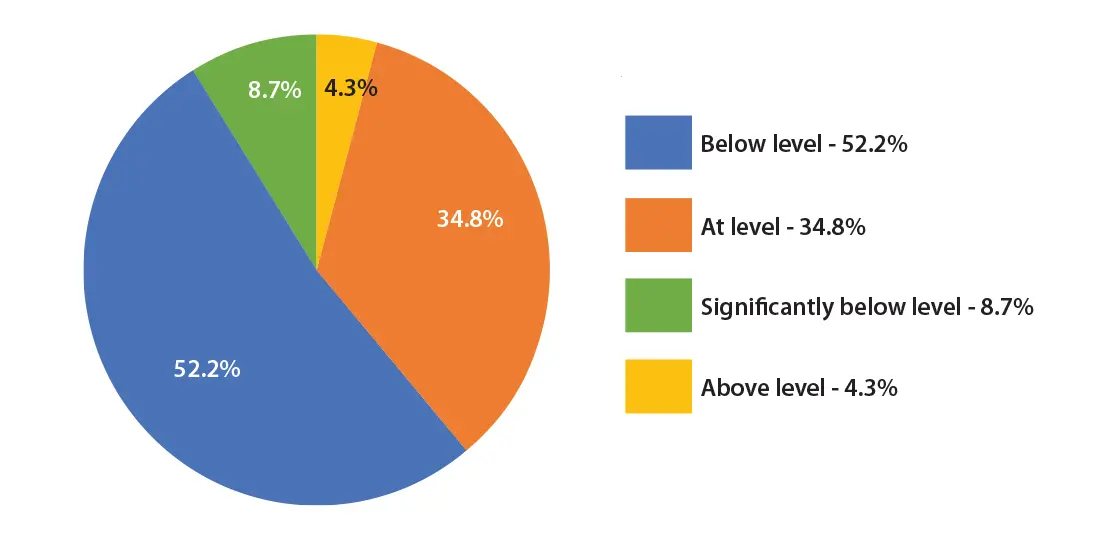

Based on your experiences, how would you describe your students' overall reading abilities?

Thanks to tests like the NAEP Reading Assessment, we have recent data that shows there’s been a marked decline in reading proficiency among students across almost all demographics and ability levels. But what are teachers actually seeing? How would they describe their students’ reading abilities based on their observations?

Related Post: NAEP Report Card 2022: Reading Scores and Resources

The majority of respondents (52.2%) said their students’ reading abilities were below level. Another 8.7% of respondents stated their students were significantly below level.

In comparison, 34.8% of respondents said their students were at level, and just 4.3% thought their students’ reading skills were above level.

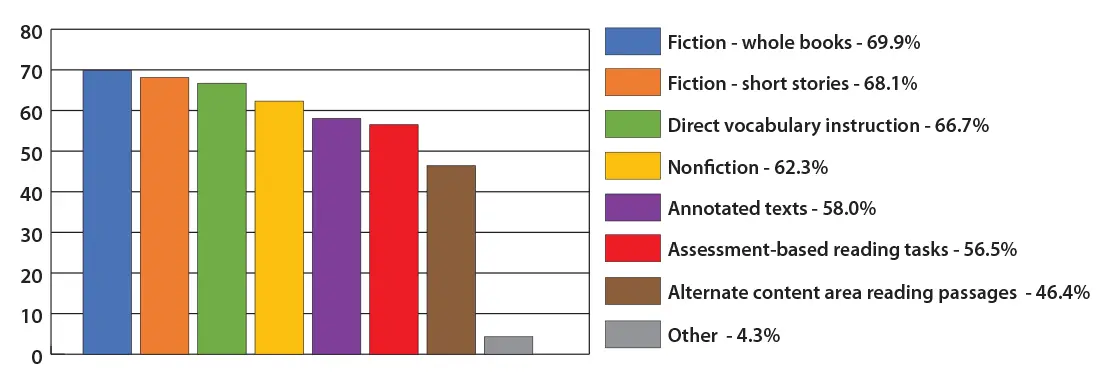

What would you like to see in a reading curriculum?

We asked survey respondents to choose what elements they’d like to see in a reading curriculum, from the types of texts used to specific learning strategies that help build literacy skills.

When it comes to text types, fiction topped the chart, with whole books (69.9%) beating out short stories (68.1%) by just a few votes. Nonfiction followed behind at 62.3%.

The two least popular text types were annotated texts (works that include comments alongside the main content) at 58% and alternate content area reading passages (texts from science, history, math, and other subjects) at 46.4%.

Related Post: 3 Ways Students Benefit from Reading Whole Books

Moving to other instructional elements, direct vocabulary instruction was a popular choice at 66.7%. Assessment-based reading tasks came next at 56.5%. Other answers included grammar practice, targeted instruction for struggling readers, and creative extension projects.

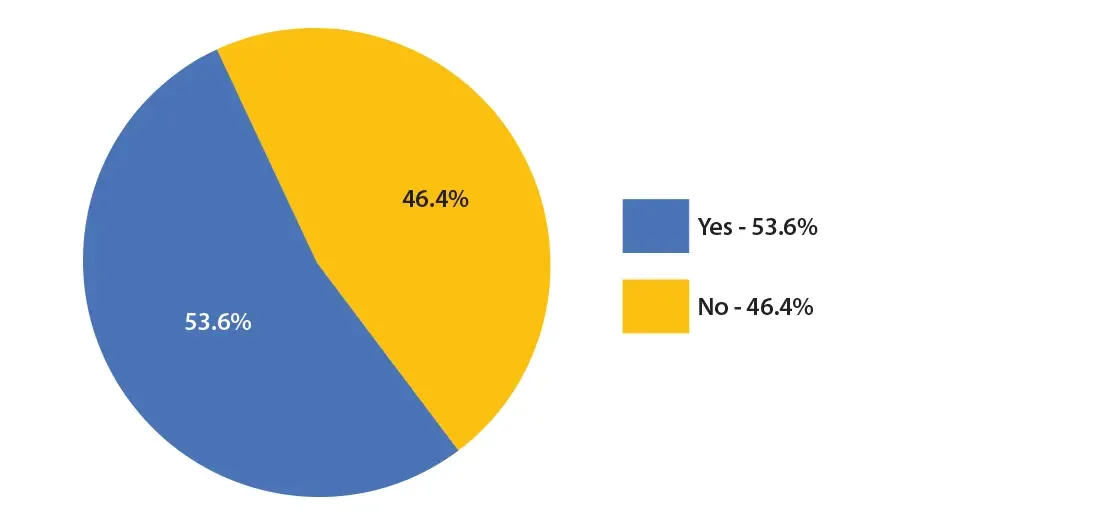

Do you assign reading tasks as homework?

There are mixed opinions about assigning reading tasks as homework. On one hand, it encourages independent reading and gives students a chance to interact with the material outside of class. However, not all students have supportive environments at home, whether that’s because of a lack of time, other responsibilities, or limited supervision by parents or guardians.

When asked if they assign reading tasks as homework, 53.6% of survey respondents said yes, while 46.4% said they do not.

What works best in your classroom to help struggling readers?

We know there’s no one-size-fits-all solution to the reading problem; what helps in one classroom might not make sense in another. We wanted to find out what teachers are currently doing in their own classrooms to get students reading.

For many respondents, guided reading and class discussions play a large role in getting their students to think critically about the texts they encounter:

“Reading together as a class, taking notes on what we read, discussing themes and topics, identifying main points and quotes, tying things to their lives from the book.”

“Reading important passages aloud in class, and full class discussion of the meaning and message.”

“Teacher-guided read alouds with critical thinking prompts; using a mix of reading strategies.”

“I have to do a lot of modeling the questions a reader needs to be asking, so there's a lot of guided instruction.”

“Teacher-directed instruction. Going through a text together and discussing it with the students.”

A number of teachers said that audio recordings and videos are good tools for helping students follow along with the text:

“Visuals. They respond well to video recaps of chapters we read in class.”

“Audiobooks help significantly. [Students] have auditory comprehension skills, but they do not comprehend what they directly read.”

“I have started using audiobooks for all novels and if available, any short stories covered in my curriculum. Because my students read on such low levels, I want them to hear what the stories should sound like when read appropriately (no mispronounced words, how sentences flow when read with correct punctuation, changes in character voices, etc.). This seems counterintuitive because the students are not actually reading the material, but I have seen a rise in comprehension since starting this. Students are required to follow along with the audio and complete any Guided Reading Questions assigned, as well as any comprehension activities tied to the stories. This method also helps to save time and move lessons along at an appropriate pace versus 'Round Robin Reading' or assigning reading sections as homework.”

Several survey respondents noted that allowing students to choose their own reading material or pick from a selection, rather than assigning a specific book, leads to more engagement:

“What works well for my students is offering options for reading material. While there are times that we all need to read as a class, students are more likely to independently read texts that allow them to explore their own interests.”

“We use a modified Reader's Workshop model of curriculum, which allows students controlled freedom for what they will be reading. Our prior curriculum only had students reading 3 novels as a class per year and students didn't do any other reading outside of that. This new curriculum has more student buy-in because they have choice.”

“Giving students a choice in what they read (when appropriate) and conferencing with each student about what they are reading.”

Other common answers included breaking reading assignments into smaller chunks, making graphic organizers, hosting literature circles, explicitly teaching comprehension strategies, phonics practice, and introducing students to multiple writing genres and styles.

What do you think of the survey results? Are you surprised by some of the responses? We want to know! Join the conversation on Facebook or Instagram.

Thank you to all of our survey respondents. Your opinions are always appreciated! We’d love to hear from you again in the future, so please keep an eye on your email inbox for more survey opportunities.

Reading

Improve reading comprehension, writing ability, and test scores with the right resources for your students.

With Prestwick House reading programs, your students will engage in active learning, using both fiction and nonfiction, to improve their reading comprehension.

Visit the Reading Portal